Making a Miter Square

07 Mar 2024It is common knowledge that a combination square can replace a bunch of conventional tools, including the miter square. Why, then, am I making my own miter square from brass, walnut, and an old saw plate?

I prepared a piece of walnut heartwood, some 5mm brass rod, 2.5mm brass plate and a piece of old saw.

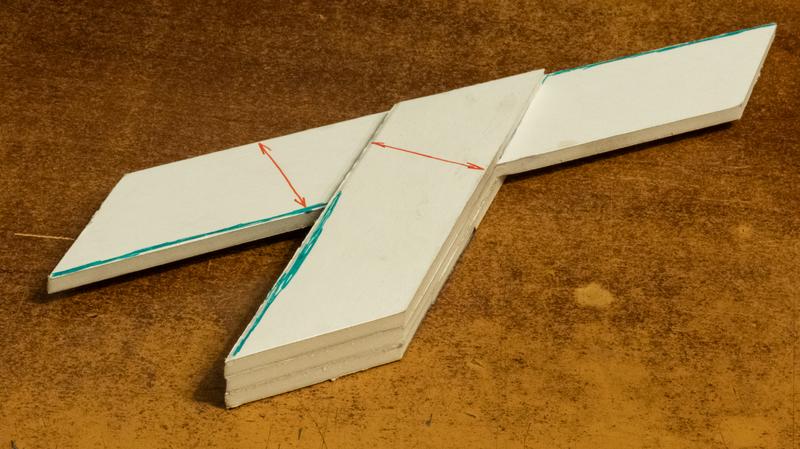

This time, I decided to start by creating a mockup from foamcore to gauge proportions and size. Concerning size, the edges of the beam marked in green determine the maximum board width this square can handle. However, in this case, the beam length was limited by the size of the saw plate material.

The width of the stock and the beam has no effect other than aesthetics. Initially, my plan was to make the stock and the beam equal in width. However, after several failed attempts to cut the beam straight, it ended up narrower than the stock, and I decided to leave it at that.

For symmetry and visual balance, I opted to match the length of the edge of the stock marked in green with that of the beam marked in green. That worked out well.

With the prototype made, I proceeded to cut the pieces to rough size.

Squaring and surfacing the wood was easy in comparison to cutting all the metal, especially the saw plate. I tried cutting it with a hacksaw at first and gave up quickly. Fortunately, I was able to use a tiny table saw with a thin abrasive cutoff disc to produce a strip of consistent width. Consistent to within 1mm, I should add, because I had to grind it to the final shape by hand. I tried to cut brass with the same abrasive disc, but the disc flexed and the cut wandered off. Not surprising in hindsight, as the steel plate was 1mm thick versus the 2.5mm thickness of brass. So, hacksaw for brass, cutoff disc for steel.

In traditional square construction, metal pieces are affixed to the wooden stock using pins and possibly screws. However, this method requires tighter tolerances and better tools than what I have at my disposal. Thankfully, this day and age offers excellent epoxy glues. I opted for the five-minute variety because its quick curing time makes it easier to hold everything in alignment until the glue sets.

Before the glueup, I applied masking tape to the surfaces that should remain clean. This proved effective. Afterward, I removed the tape and any excess glue while the glue was still soft. It fully hardens within 24 hours, so the following day, I filed down any excess brass and then sanded everything flush and square.

I have glued a strip of fabric-backed abrasive to a piece of particle board, and that became my grinding surface. With this simple tool I was able to get one of the edges of the beam flat. I held the flat edge against a metal ruler and there were no visible gaps. With one edge ground flat, I could grind the other edge to be flat and parallel to the first edge. Making it flat was not difficult; I simply rubbed it back and forth on the abrasive surface. To ensure parallelism, I regularly checked the width of the strip and applied more pressure where material needed to be removed.

I finally reached that dreaded moment when I needed to make the slot in the stock. I could not trust the table saw because of its low power, so I had to cut the slot by hand. I did my best to make a jig to guide the cut. Even with the jig, I was off by about 0.5mm in one of the corners. The thickness of the hacksaw blade was about the same as the beam, but since I did not cut the slot perfectly straight, the beam actually fit quite snugly.

However, that was not my intention, so I enlarged the slot a little bit to achieve a sliding fit. I then mixed up the epoxy and glued the beam in place, using a known good combination square as a guide. I did not use any clamps, just held it in my hands for several minutes until the glue became hard enough to release it.

At this point, the square was perfectly usable and as accurate as I could make it. However, I then decided to add the brass pins, which did not turn out as I expected. The drill bit went through the wood easily, but the saw plate was too hard for it. I suspect that making a divot with a punch would have helped, but I did not have a punch that small. I won't bore you with the details, but after dulling three drill bits and breaking four, I finally managed to get through.

I peened the brass pins, sanded everything flush one more time, and applied some finish. For the finish, I chose Danish oil. I tried waxing the square afterwards, but that almost ruined it. The white carnauba wax seeped into the pores, and since the buffing action does not reach so deep, it remained white. On a dark wood, this is pretty ugly. Fortunately, I was able to wash out the wax using solvents, and then applied several thin layers of diluted varnish.

This has certainly been quite an experience. In the end, it's undoubtedly a success, but I've come to learn that the saw plate does not lend itself to drilling easily. Considering everything is securely held together with epoxy, the brass pins aren't truly necessary. Nor are the wear plates, as it would likely take decades of regular use to noticeably wear out the wood. Nevertheless, walnut and brass complement one another beautifully, and the slightly pitted saw plate aligns perfectly with the vintage aesthetic.

DIY Blog

DIY Blog