Stanley Plane Adjusting Nut

13 Dec 2023One of my Stanley bench planes had a small adjusting nut that was challenging to reach and turn, especially with the same hand that's holding the plane by the tote. Sure, I could have bought a replacement, but where's the sport in that?

Creating a new nut from scratch would have been too demanding given my available metalworking equipment and skills. Not only would I have to machine the nut body from solid brass, I would also have to make internal 9/32" 24 TPI left-hand threads with a tap that I do not have. So, I settled on modifying the existing nut by increasing its diameter with additional material.

I faced two decisions: selecting the material and determining the method of attachment. I weighed options between metal, plastic, or wood and considered press fitting, gluing, using mechanical fasteners, welding, or soldering. Ultimately, I chose to solder a piece of brass to the nut and machine the resulting assembly as a single piece.

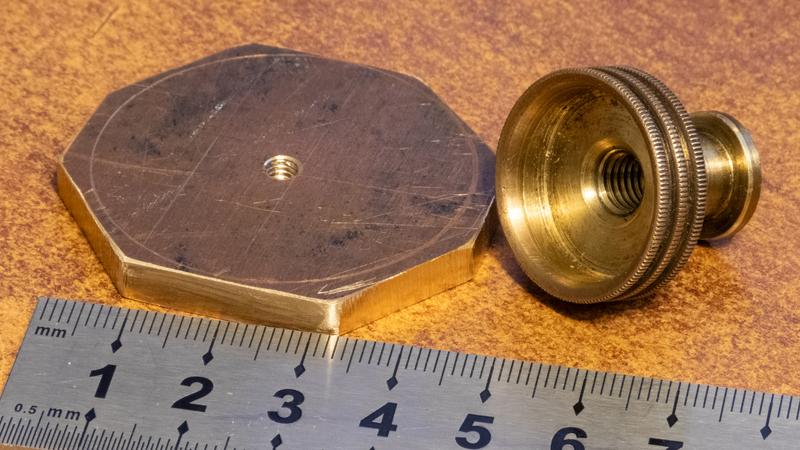

Initially, I removed the knurled part from the nut and machined its face flat. Precision in shaping the part was less crucial as long as the surface was clean for a solid solder bond. I turned a flat disc from some brass stock and machined a recess to hold the nut. Though I anticipated a snug fit, my measurements fell short, leaving a visible gap between the parts. Ironically, this gap became instrumental as it allowed for solder fill-up during the process.

For soldering, I opted for the standard low-temperature 60% tin / 40% lead solder commonly used in electronics. Given the operating conditions, this bond is likely as robust as the material itself under regular use.

Beginning with tinning the parts using flux and solder, I experimented with a propane torch initially on the disc, but that was a mistake. I could not get the part to heat up without burning the flux. However, I discovered that my 80W soldering iron easily brought the assembly to the required temperature, it just took some time.

Because of the loose fit between the parts, I had to make a fixture to hold them while soldering. I turned a small rod to hold the parts concentrically. With both parts tinned and with plenty of solder on the tip of the soldering iron it was easy to get all of the solder to liquify. While the solder was still liquid, I wriggled the nut with a wooden stick to make sure that I was not leaving any voids between the parts. Then I let the solder cool down and solidify. It took surprisingly long, as the parts seemed to have a significant thermal mass.

Once the assembly cooled down, I removed it from the fixture and used solvent to clean it. The disc was coated in scale and flux residue, while the nut remained clean as I didn't expose it to an open flame during soldering.

To secure the part in the lathe, I devised a fixture using a simple M6 screw. This setup allowed me to clean up both sides of the disc. I made sure to stay away from the bits that are used to drive the adjustment yoke in the plane - they were growing sloppy from years of use, so I could not afford to remove any more material there. Fortunately, no cleaning was necessary for that part.

In absence of any requrements to the disc's dimensions, I machined it down to reveal clean bare metal while tidying up the outer diameter simultaneously.

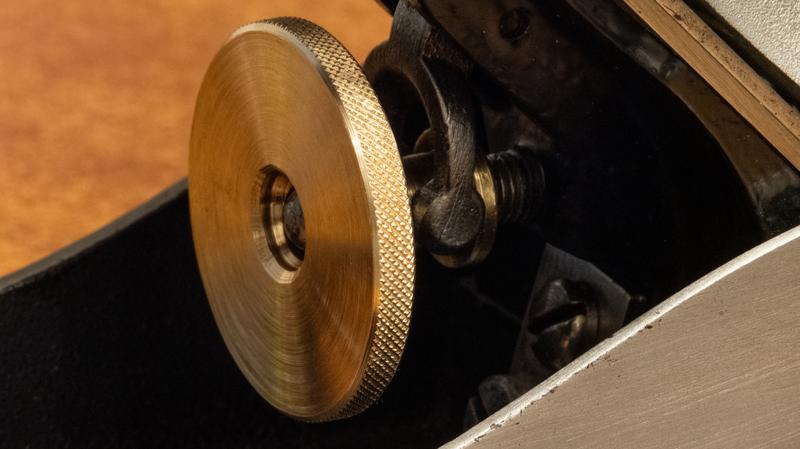

After cleaning up the part, I knurled the outer edge of the nut to improve its grip. Ultimately, that was the objective of this entire endeavor: to make adjustments easy.

As the newly modified part finds its place within the plane, the impact on its usability is remarkable. These small improvements bring a world of difference to the convenience of a tool.

DIY Blog

DIY Blog