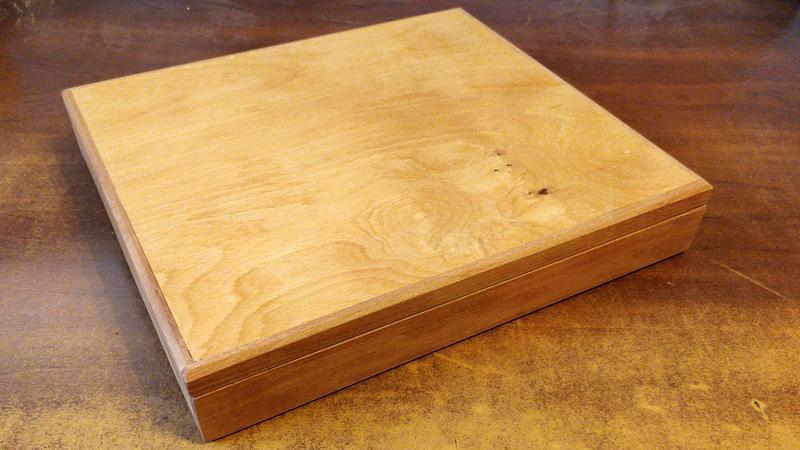

A Box For Chisels

21 Oct 2022I've always meant to make a nice box to hold my chisels and finally found the time. I did not have any particular plans, just made things up as I went along, trying out new joints and techniques. Besides, it's always easier to pretend that the thing I got was the thing I wanted than to explain what went wrong.

The box was made from reclaimed wood, some drawers from an old cabinet. It looked like beechwood to me, and the plywood bottom was actually veneered to match the drawer sides. Unfortunately, some boards were laminated together from several narrower pieces, but there was enough material to get by.

When I began, I only had a rough idea of how big the box would be. In the end, it holds my six chisels and has space for two more. Clearly, there are ways to situate them in a more compact manner, but there is no need for that.

I started by ripping the boards to the same width, then edge-planing them. For boards this short, any plane would be like a jointer plane. The exact width of the boards did not matter, as long as it was the same for every board. I decided to first assemble the box, then cut it apart to separate the lid.

The tiny rabbets go at the top and at the bottom of the boards. These rabbets would hold the plywood, so they needed to be as deep as the plywood was thick. Their width did not matter much, but I decided that half the thickness of the board would be the way to go. They were cut with a combination plane, which was probably better suited for grooving, but since it had the depth stop and the fence, and the rabbet was pretty narrow and along the grain, it all worked out well.

With the boards prepared this way, I cut them to length. Two pieces needed to be exactly the same length and have very square and true edges. A shooting board really helped me here. On the other two boards, I made additional rabbets at either end, this time across the grain. (They are marked as waste in the image above.)

Fortunately, the width of these cross-grain rabbets does not matter much, as long as the distance between them is the same on both boards. This played to my advantage, as I made these cross-grain rabbets about twice as wide as they needed to be. This greatly aided the stability of my shoulder plane, allowing for more consistent depth. As for the overhang, it would just get trimmed later.

With these parts done, I could start the glue up. I actually glued the frame together first, because it would make it easier to fit the plywood pieces into the already established recesses. The rabbet joints in the corners were easy to align, and I got the whole frame assembled. This turned out to be the best time to prepare the little boards that help seat the chisels in place. They were actually inset into the frame, in other words, the frame had tiny mortices to hold these boards. It would have been much harder to cut these mortices if the plywood bottom were already glued in place.

I drilled a row of holes in the taller board and then made some saw cuts. The shorter board was shaped with a rasp. I sanded both boards a little bit, but clearly not enough to get rid of all the saw marks. I then fitted the plywood to the top and bottom recesses. Cutting the plywood with a saw causes considerable tear out, but I intentionally made the plywood piece larger and then removed the last bits of waste with a plane.

At last, I glued the whole box together. I then carefully cut it open, separating the lid.

I've learned that no matter how careful I was with the saw and how fine the saw teeth were, the mating surfaces would still need a lot of planing to have the box close without a visible gap.

Then came the time to install the hinges. I wish I could find better hardware for the box. There were two kinds of hinges available: either flimsy, light-duty stuff intended for arts and crafts, or really big, heavy hinges suited for doors or maybe crates. I had to settle on these, the smallest of the heavy-duty kind.

The hinges were clearly meant to be installed differently, as they were designed to fit a box with a wall at least 16 mm thick. Mine was around 10 mm, so I had to improvise. I had to recess the hinges into the back of the box to make them work. Also, the factory either drilled the countersinks with an incorrect tool, or my screws were too large, as they did not go into the countersunk hole all the way. Finally, I could not find a suitable latch for the box, as the only good ones I could find were too large.

With the hinges in place, I disassembled the box again and chamfered the visible edges. There is a certain charm to these somewhat uneven, hand-cut chamfers. With the chamfers cut, the box was treated with some oil-varnish blend and left to dry. Since it was pretty cold here, the box took a long time to dry, so for now I decided not to do a second coat. I might add another coat later. The advantage of an oil finish is that it can be easily reapplied again with little to no preparation.

This project had a lot of "firsts". So what have I learned? Plenty.

- I need a coarser saw for rip cuts. Even with my 8 TPI saw, ripping, let alone resawing, is a chore.

- On that note, it's time to get a few good boards, instead of making things from scraps.

- More clamps and/or a vice. Enough said.

- The combination plane can adequately cut small rabbets along the grain. Perhaps attaching a wooden strip to make the fence wider would further improve stability - got to try that.

- I enjoyed cutting the cross-grain rabbets with a shoulder plane when a strip of wood was clamped to serve as a guide. This means I don't really need the fence for this plane, which I don't have anyway. However, this wooden guide also obstructs the side where the depth stop (which I don't have either) is attached. I guess I'll just practice planing to the line.

- My primitive shooting board setup is good enough to true up the end-grain edges of wide and thin boards, but inadequate for anything else. Clearly, I need a better shooting board and a dedicated shooting plane. This will probably be my next major tool-building project.

- The joinery in this box is nothing but pragmatic. But putting some dowels through the rabbet joint would reinforce it and might make it look better. And I definitely need to up my game: try dovetails for the corners and raised panels for the top and the bottom.

- I wonder if gluing the box first and then cutting it open was the best idea. Perhaps I could run a shallow rabbet along the edge where the lid meets the box. It would look nice, but there was no way I could make that after the box had been assembled. I definitely need to explore these possibilities.

- Carving, pyrography, or some other decoration would be nice. A simple geometric ornament should not be hard to engrave.

- I need a source for better hardware. Or I need to start making bigger boxes.

- The box still needs a latch and maybe another coat of finish.

Most importantly, I need to continue making things. Now is not the time to stop.

DIY Blog

DIY Blog